By Joshua Blakeney

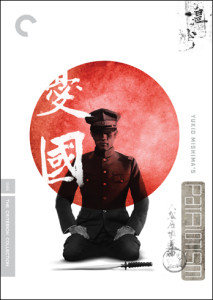

The above video presents the filmic rendition of Yukio Mishima’s play Patriotism (1961). An English-language copy of the radical nationalist play can be obtained here.

Patriotism depicts the final hours of the lives of Takeyama Shinji and his loving spouse, Reiko, whom, upon being entangled in the partisanship inherent to the abortive coup d’état of February 26, 1936, resolve to commit ritual suicide. Mishima deftly captures the tension and spasms of emotion that would afflict any couple seeking to fill their final hours prior to committing seppuku.

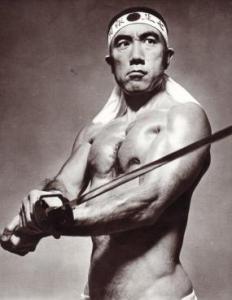

Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) was a Japanese author, playwright and political philosopher who staged a symbolic coup d’état in November 1970, with the ostensible goal of reinstating Japan’s traditional Emperor-centered political system. He committed ritual suicide after the uprising failed to gain traction.

The reader agonizes as he witnesses a passionate, recently-wedded couple having to make the ultimate sacrifice of subordinating the personal for love of Emperor and nation. “This is neither a comedy nor a tragedy” said Mishima of Patriotism, “[t]o choose the place where one dies is. . .the greatest joy in life. And such a night as the couple had was their happiest. Moreover, there was no shadow of a lost battle over them; the love of these two reaches to an extremity of purity, and the painful suicide of the soldier is equivalent to an honourable death on the battlefield.” The healthy copulations of the couple and their submission to ritual is almost deployed metaphorically by the revolutionary conservative as a perceived microcosm of organic nationhood, one feels.

The two factions of the Imperial Army which clashed in the Ni Ni Roku Incident were the restive Kōdōha, or Imperial Way Faction—who wanted to strike north against the Soviet Union—and the more established Tōseiha, or Control Faction, which wanted to strike south against Dutch and British possessions primarily. The coup was spawned by an attempt by the Tōseiha to have many of their Kōdōha rivals deployed to Manchuria to remove them from Tokyo, where all political decisions of any import were made. The Kōdōha, instigated the uprising to prevent that marginalization from coming to fruition and to ultimately institute certain reforms.

The leaders of the coup agitated for what was termed a “Showa Restoration” to reinstate a more organic and indigenized political process to the Nipponese archipelago. There was a perception that many of those who were in the immediate inner circle of power were foreign educated and were seeking to apply alien, extrinsic values to Japanese society. The insurgents wanted to establish a more physiocratic society wherein the peasantry would be unified with the Emperor in a soft form of Shinto authoritarianism. This initiative would be the optimal means of stabilizing Japan at a time when Internationalists were extensively meddling in Asia, they believed.

Lieutenant Takeyama, in the play, intuitively sides with the Kōdōha over their rivals, thinking them to be more authentically patriotic, but knows he is to be mobilized the next day to lock horns with its members, as the Emperor had arbitrated in favour of the entrenched Tōseiha faction which intended to promptly crush the rebellion. Not being able to bring himself to put down the proponents of the Showa Restoration, the young Lieutenant is forced to decide to end his and his wife’s lives.

Lieutenant Takeyama, in the play, intuitively sides with the Kōdōha over their rivals, thinking them to be more authentically patriotic, but knows he is to be mobilized the next day to lock horns with its members, as the Emperor had arbitrated in favour of the entrenched Tōseiha faction which intended to promptly crush the rebellion. Not being able to bring himself to put down the proponents of the Showa Restoration, the young Lieutenant is forced to decide to end his and his wife’s lives.

One of Mishima’s radicalisms was his post-war support for the Young Officers who instigated the Ni Ni Roku attempted seizure of power. Mishima, like the insurrectionists, believed that Emperor Showa (Hirohito) had been under the influence of corrupt, foreign educated usurpers and that patriotic Japanese nationalists within the military had had a duty to sweep aside those who were misguiding the nation. Mishima would become controversial in Japan for his criticism of the Emperor’s suppression of the rebellion and his total submission to the American invaders.

The black and white film, which appeared in English under the title of The Rite of Love and Death, was produced by Mishima in the ancient Noh dramaturgical form. Like many radical rightists, Mishima was skilled at melding the classical with the modern to produce a revolutionary aesthetic which was still traditionally oriented.